What Not to Say To Bereaved Parents

by Laura Storey

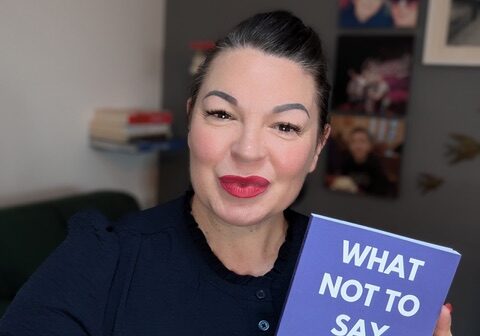

Kiki Deville's new book is a guide to supporting bereaved parents

Australian-born singer, songwriter, and performer Kiki Deville, who gained fame in 2014 as part of Team Will.i.am on The Voice UK, is now adding writing to her list of talents. Known for her burlesque and variety performances, Deville has written a new book, What Not to Say: A Practical Guide to Supporting Bereaved Parents.

“This isn’t a book about death. This is a book about love,” says Kiki. If you’ve read her debut book, What Not to Say: A Practical Guide to Supporting Bereaved Parents, you’ll understand this sentiment completely. Deville pours love into every page—not only for her son, Dexter, who passed away in 2007 at just one month old from the rare genetic disorder Zellweger Syndrome—but also for bereaved parents everywhere. They face the challenge of navigating well-meaning but often hurtful comments from others who may not know the right words to say.

“A baby is not replaceable, and these comments do nothing to ease the grief.”

“In the years since Dexter’s death, I’ve become part of a club that no one wants to join,” Kiki explains, referring to the community of bereaved parents. As a patron of Chorley’s Derian House children’s hospice, where Dexter spent his final days, she regularly speaks with grieving parents. She has found that many of them, like her, have had to endure unintentional yet painful remarks from others.

Kiki’s son Dexter

“One of the things people often say is, ‘At least you have other children’ or ‘At least you can have another one,’” Kiki says. “But you wouldn’t say that to a widow. You wouldn’t say, ‘At least you can have another husband.’ Just because you can have another baby doesn’t mean it will replace the child you lost. A baby is not replaceable, and these comments do nothing to ease the grief.”

Deville stresses that while these remarks are rarely malicious, they stem from a lack of understanding. Her personal experiences and conversations with other parents shaped her book, which is not just about what not to say but also about how to offer genuine support.

“No one says these things out of malice,” she reiterates. “They say them because they want to connect. But because we don’t talk about death or grief openly, people aren’t given the tools to say something more supportive. For example, instead of offering well-meaning platitudes, you could say, ‘I can’t imagine how difficult this must be for you. Would you like to talk about it? Would you like me to listen?’ Simply being present can offer real companionship.”

While saying the wrong thing can be hurtful, not acknowledging the loss can be even worse.

“If I mention my son’s name, people often become uncomfortable. The death of a child forces us to confront our fears about losing a child, so people tend to avoid the topic,” Kiki explains. “But losing a child is incredibly lonely. You usually talk about your children daily. When a child dies, you can go weeks, months, or even years without hearing their name.”

Kiki’s message is clear: saying a child’s name matters. “By mentioning our child’s name, you permit us to feel and reflect on our grief. It’s a profound gift.”

She shares stories from her friend Sarah Parsons, whose daughter Maggie was stillborn. “Sarah told me that after Maggie’s death, people stopped talking to her about everything, not just her daughter because they thought any conversation would upset her.”

Dexter with his parents

Though the book is invaluable for bereaved parents, Kiki stresses that it’s written for everyone. “In the UK, between eight and 15 stillbirths occur daily, alongside ten child deaths, while one in four women experience miscarriage. It happens far more than we want to believe,” she says. Supporting bereaved parents is something we’ll all likely face at some point, and Kiki believes it’s not fair to expect parents in grief to teach others how to help.

To make this difficult subject more approachable to a wider audience, Kiki drew from her background in variety, cabaret, and burlesque. “It was important for me that the book felt accessible—and even funny at times,” she adds. To help bring levity to such a heavy topic, Kiki collaborated with comedy writer Sarah Mills, who was diagnosed with bowel cancer in 2018 and turned her treatment experience into a chat show hosted from a chemo ward.

Together, they found ways to inject humour into the book. “I found that quite liberating being able to bring that side of me into it.”

Despite her creative background, this is Kiki’s first book. “A friend of mine, Heidi Mavir, wrote a book last year called Your Child Is Not Broken, and she always told me I needed to share my story,” Kiki shares.

“We realised that no one had ever told people we wanted them to say our children’s names. So I thought, ‘Let’s tell them why it matters.’”

Heidi’s book, a Sunday Times bestseller, chronicles her journey of discovering her child’s neurodivergence. Kiki and Heidi met in the world of burlesque, but Heidi also works with Authors & Co., a company that helps writers achieve their goal of publishing non-fiction books. “Heidi was instrumental in encouraging me to write my book,” Kiki says.

Writer Kiki deVille

The idea for What Not to Say emerged while Kiki was working on a campaign for Derian House Hospice that encouraged people to say the names of deceased children. “We realised that no one had ever told people that we want them to say our children’s names. So I thought, ‘Let’s tell them why it matters.’ Everything fell into place after that.”

What Not to Say: A Practical Guide to Supporting Bereaved Parents was published on September 12, 2024—what would have been Dexter’s 17th birthday. Kiki made a promise to her son in his final moments that he would change the world. With this book, she hopes that bereaved parents will feel more supported, understood, and less alone in their grief.

“It is a book about love and understanding; I want to take people on a journey from pity to empathy and hopefully give them the tools to make everyone’s experience just that little bit easier,” Kiki explains.

You can get your copy now on Amazon for £5.99 on Kindle and £10 for a paperback.